CGER at the heart of education savings in Belgium: Growth, war and the school pact

The movement for education savings in Belgium began in Ghent. The city encouraged the practice beginning in 1858, which was boosted by a university professor and freelance lawyer, François Laurent. In 1865, the city made provision to institute a special fund to provide savings books to students of free municipal schools. This action was tied closely to the founding of the Caisse Générale d’Epargne et de Retraite/CGER (a forerunner of BNP Paribas Fortis) by the Minister of Finance Frère-Orban. Created the same year in response to the glaring poverty in the working class, this social project developed by the progressive wing of liberalism wanted to teach people how to save. Consequently, it was not surprising that the Caisse Générale took an active interest from the beginning in education savings.

To ensure it was implemented successfully, the teaching profession attended conferences on best savings practices. At the same time they taught children how to read and write, they taught them how to save every week in the field. The teacher deposited students’ instalments every week or month at the CGER. And even if the average deposit was not very high, 139 francs in 1863, the number of transactions continued to increase and other towns followed Ghent’s example. In 1868, nearly 200 Belgium towns participated in this new apprenticeship.

In spite of a few reservations in the face of this teaching, which would create – according to certain criticisms – greed , theft and stinginess from early childhood, the principle of education savings grew beyond Belgium and spread to its nearest neighbours up to Zeeland.

Translated into several languages, the writings and brochures of Professor F. Laurent testify to the success of this project. Awarded in 1872 for “the best work or best invention that could improve the material or intellectual position of the working class in general,” the promoter of education savings saw a means to ward off misery, offering the most destitute recourse to the poor-relief bureau and almshouses.

And everything seemed to confirm it, since education savings grew without hitch for several decades.

But in 1954 education savings suddenly became the stake in a political fight between the Christian-Democrats and the other parties. After four years in power, the Social-Christian Party (PSC) lost the elections to the Belgium Socialist Party (PSB). A Church – State split appeared and the PSC organised a strike to express its disagreement with the government’s education projects, including in particular the drastic drop in public subsidies. Teachers mobilised, stopping education conferences and all education savings. A boycott that ran counter to a public initiative, the CGER. An educational war broke out, ending four years later with the law of 29 May 1959 ratifying the School Pact. The agreement between the parties made it possible to move towards the democratisation of education, thereby guaranteeing educational peace in the country.

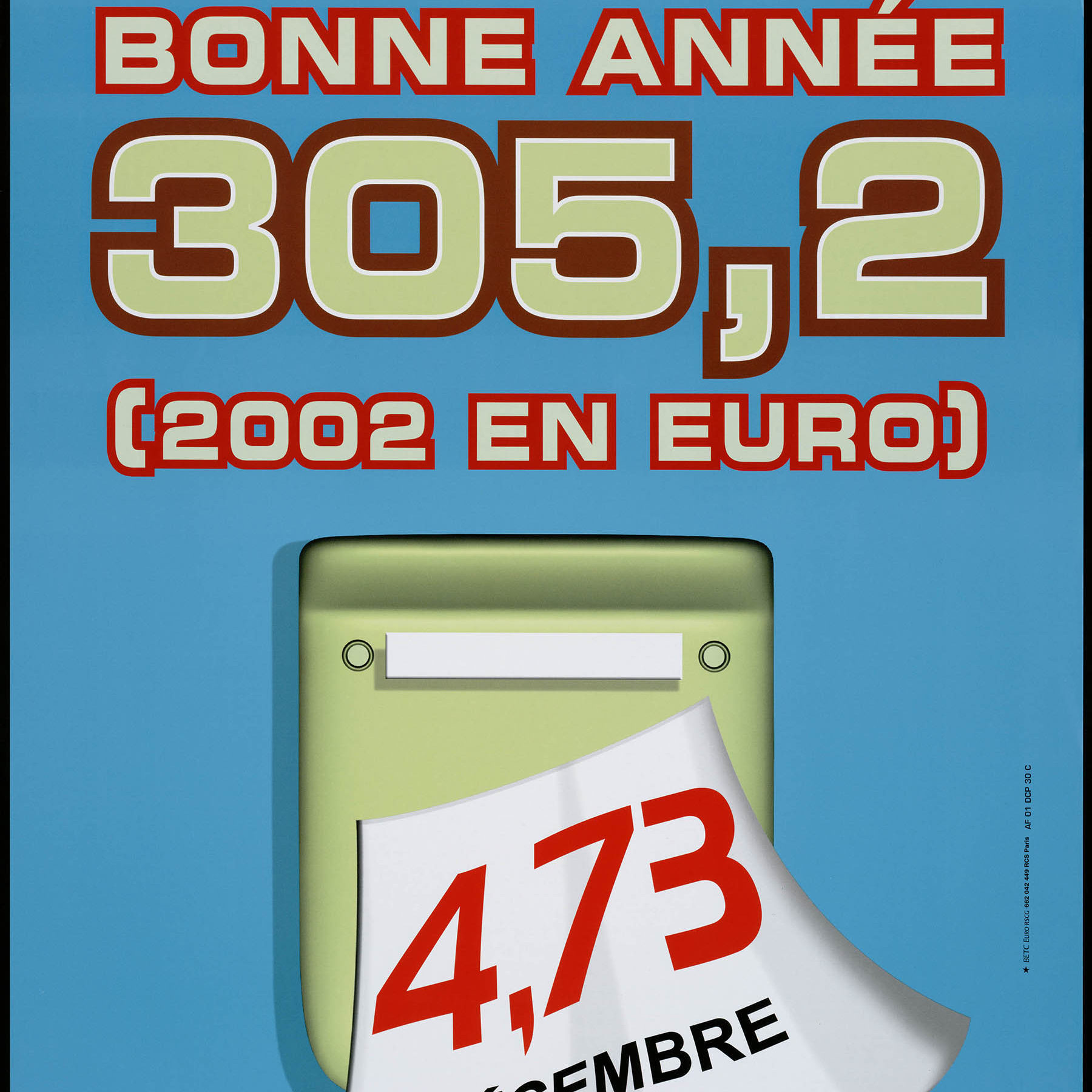

However, having lost its monopoly after the Second World War and being weakened by the educational war, the CGER had to reinvent itself. Even if young people’s deposits represented half a billion in 1963, it decided to gradually despecialise and transform itself into a public bank and insurer in 1980. Education savings were finished, but young people remained key in its development strategy, as one can see in 1990 with this ad in favour of the club account 001 for 16-24 year-olds.