The Evolving Bank: How Technology Has Revolutionized the Industry

Each generation of workers corresponds to a new wave of technologies that profoundly transforms the world of work. In the banking sector, the 20th century was marked by the emergence of autonomous machines capable of performing complex calculations with great precision and without errors. This technological revolution was able to raise concerns about the impact on jobs, but it also opened up new perspectives for employees. Let’s take a look back at these developments in the profession since the mechanographic revolution.

The Mechanographic Revolution

In the mid-1920s, a new technology from the United States profoundly transformed office work. This was the arrival of mechanography, mechanical and then electromechanical machines that allowed for the automation of calculations using reusable punched cards.

This innovation perfectly met the needs of banks, which adopted it immediately. It greatly simplified administrative tasks.

Did you know?

Mechanography originated in the United States, where the first machines were invented for the population census in 1890.

Before mechanography, all documentation was written by hand. For each bank, this meant counting several tons of paper per month, making human errors inevitable. However, the growth of banking in France over time increased the volume of writings. It became urgent to automate work.

In 1926, the Comptoir national d’escompte de Paris (CNEP) spent 2.6 billion francs to purchase its first 90 accounting machines. A bold decision, as it was a pioneer among French banks. And it was a success! Just ten years later, all CNEP branches were equipped with accounting machines, punched card machines, tabulators, and check sorters.

Like any innovation, mechanography brought its share of concerns and drawbacks. The profession of “clerk” was threatened but did not completely disappear. In reality, machines were not used for all operations because they were still complicated to manipulate. The card catalog drawers were heavy to handle, and the mechanism was very noisy.

The Banque nationale pour le commerce et l’industrie found the best way to take advantage of this new technology. Under the impetus of its General Manager, Alfred Pose, it opened its first regional administrative centers in 1934, where mechanographic machines were centralized. This was the birth of “back offices”.

The bank gained in productivity and relieved branch staff, who could focus fully on customer advice. However, these places became real factories where work was rationalized to the extreme. They would become the hub of future strikes. The workforce was essentially female.

Mechanographic Operators

This photograph of the Parisian administrative center of the BNCI dates back to 1952. Mechanography was then at its peak, and the profession was learned directly in technical colleges and high schools. Over the next five years, the arrival of computing would be a real revolution for these employees.

Photo: Barbès, portfolio service, BNP Paribas Historical Archives (10Fi60-1) BNP Paribas Historical Archives

From Mechanography to Computing

In the 1950s, mechanographic machines continued to improve. But two innovations would forever bury mechanography: programming and binary language. This was the arrival of computing.

Programming automated the machine even further, making it capable of performing pre-registered orders on its own. The shift from decimal to binary language allowed for the creation of more complex programs and, above all, enabled machines to communicate with each other.

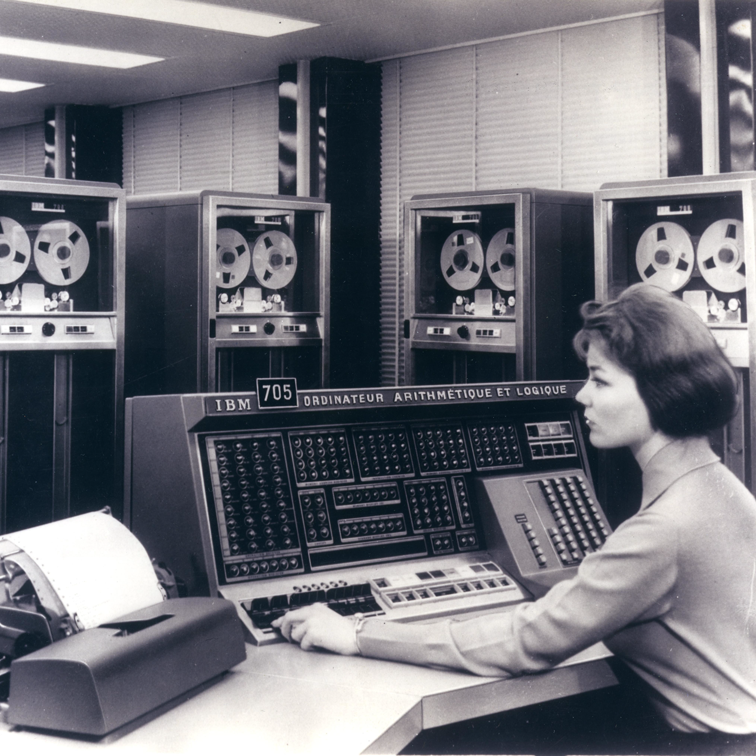

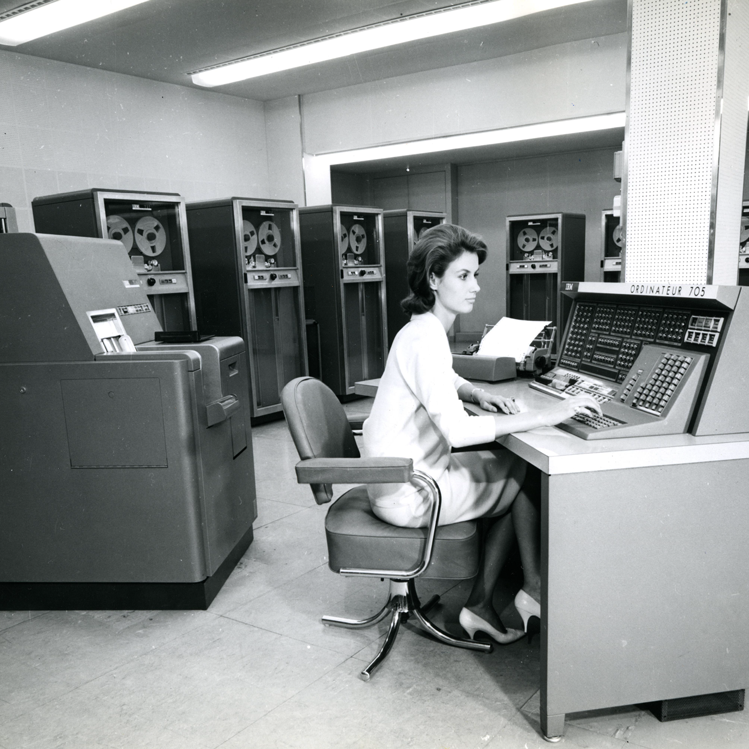

Banks and credit institutions did not miss the innovation train! As early as 1957, the CNEP ordered the Bull Gama 60, the largest European computer. In 1958, it was the BNCI that deployed the IBM 705 over 200 square meters at its data production hub.

This new, extremely efficient equipment, capable of processing 30,000 commercial effects per day, allowed banks to keep pace with the banking of French society. But it was also a major asset for the image of banks! The computer was modernity, and the promise of exceptional service for customers. The CNEP, with its then-reputedly conservative methods, did not miss the opportunity to communicate about it.

As with the arrival of mechanography, this transformation of work methods raised concerns. These concerns would intensify in the 1980s, when the invention of the microprocessor would generalize the use of desktop computers.

In this excerpt from the film “Computing at BNP” from 1987, M. Lévy-Garboua responds to the concerns of colleagues who are worried about being replaced by computers.

And to think that we are already approaching the dawn of the internet!