Two years in the STO in Germany

An employee of the Banque d’État du Maroc (BEM – State Bank of Morocco) in Paris, Claude Dené (1923-2013) was conscripted in 1943 to work for the Service du Travail Obligatoire (STO). During his two years in Germany, he wrote to his employer about the working conditions, deprivations, waiting around and small gestures of solidarity that made it possible to bear. This is his story, which is part of the tragic and often unknown history of the 600,000 French people forcibly sent to Germany between 1942 and 1945.

A young caregiver hired by the BEM

Claudius (“Claude”) Dené was born in Paris on 21 March 1923. Born into a modest household, he began supporting his widowed mother and younger sister from an early age by taking on various odd jobs, which he continued once he reached the age of 16. On 15 January 1942, at the age of 18, he was hired as an intern office boy at the Banque d’État du Maroc (BEM) in Paris. Quickly appointed as an accounting clerk, his career was interrupted by a summons, received on 1 March 1943, to join the STO. The next day, he boarded a train to an unknown destination.

Establishment of the STO in France

From “Relief” to conscription

In the autumn of 1940, the Vichy regime encouraged volunteers to travel to Germany to work. At the same time, in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region, which was administratively attached to Belgium, the Germans organised labour round-ups.

In 1942, barely 100,000 French people responded to the call, a long way off the target set by Fritz Sauckel, who was responsible for mobilising labour for the Reich. To make up the shortfall, Pierre Laval, head of the Vichy government, established the “Relève” (“Relief” programme) on 22 June 1942: for every three volunteers going to work in Germany, a French prisoner of war was released.

The Service du Travail Obligatoire (STO)

But this system was not enough to meet the Reich’s demands for labour. On 4 September 1942, a law instituted compulsory conscription: all men aged 18 to 50 and single women aged 21 to 35 were required to work in Germany. On 16 February 1943, the STO was established. It imposed two years of service on young men, first those born between 1920 and 1922. The initially planned deferments were soon abolished. Born in 1923, Claude Dené was among the first conscripted.

Between June 1942 and August 1943, 600,000 men were sent to Germany. Others, although required, remained in France to work on strategic projects such as the Todt line (the “Atlantic Wall”).

Gradually, however, the system began to break down, as conscripts escaped, refused, went into hiding, joined the Resistance or were recruited by companies working for the occupying forces. Young French people attempted to escape enrolment at all costs.

The toll on France was heavy: of the 600,000 conscripted by the STO, between 25,000 and 35,000 lost their lives, half of whom were shot, hanged or beheaded for acts of resistance. Some died in bombed factories, in concentration camps or from ill-treated illnesses or workplace accidents.

The STO left its mark on many lives, including those of Antoine Blondin, Georges Brassens, Raymond Devos, Michel Galabru, Alain Robbe-Grillet and François Cavanna.

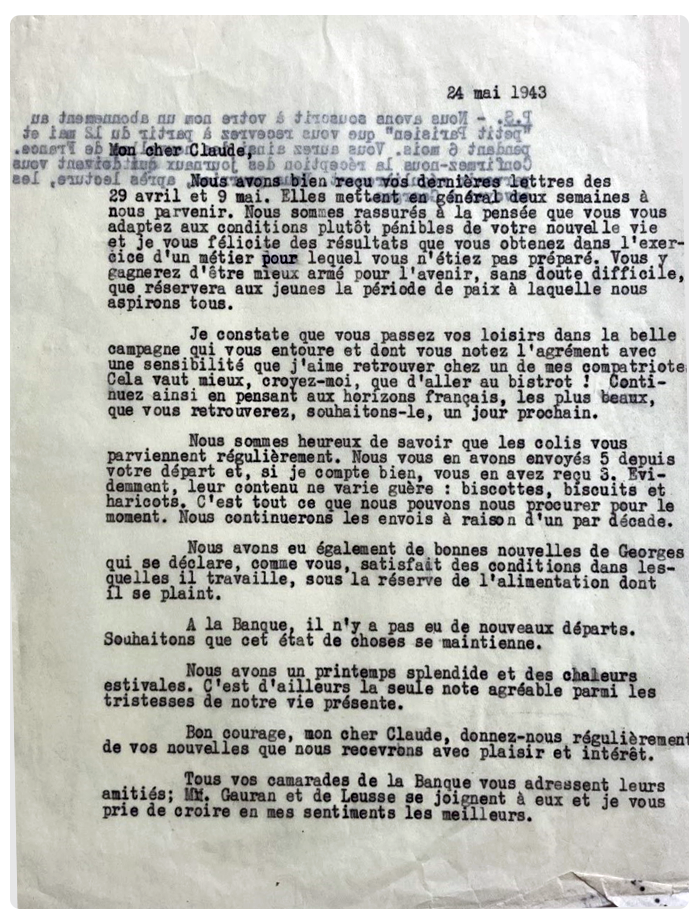

Between 1943 and 1945, Claude Dené and his employer at BEM maintained their connection by exchanging mail on a very regular basis. The letters sent by the Bank were accompanied by packages, intended to somewhat ease Claude’s exile and help him better cope with his condition as a conscripted worker…

Claude Dené, conscripted worker in Germany

“I’ve just completed a pretty long five-day journey interspersed with stops,” he wrote as he arrived in Friedrichshafen, on the shores of Lake Constance. Housed in a barracks camp three kilometres from his factory, he learned the job of machine turner.

Food was scarce: potatoes and 300g of black bread per day. What worried him most was separation from his friend and colleague Georges Bellon at a triage station near Stuttgart. The Bank had sent him his address in Esslingen-Neckar and a correspondence sprang up between them, although it would end after a few months.

The work was punishing: 11 to 12 hours a day, six days a week. As spring returned, Claude explored the nearby woods. His letters then took on a subtle poetic tone. He regularly received parcels from the Bank (biscuits, beans, pâté), and a subscription to Petit Parisien, although the newspaper arrived late.

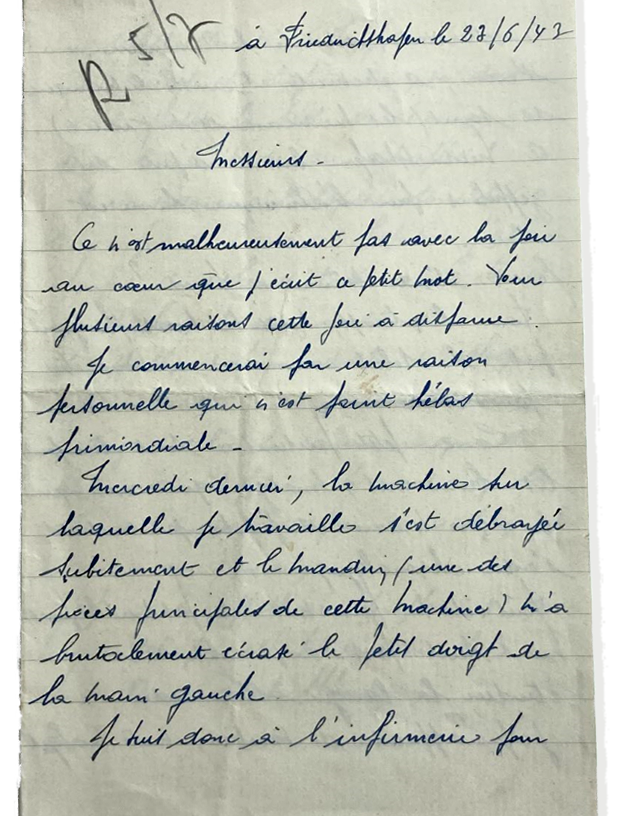

Having injured his finger in June 1943, he was moved to night work. The camp population was growing with the arrival of workers from all over Europe: Russians, Poles, Dutch, Italians.

A harsh winter, bombings and displacement

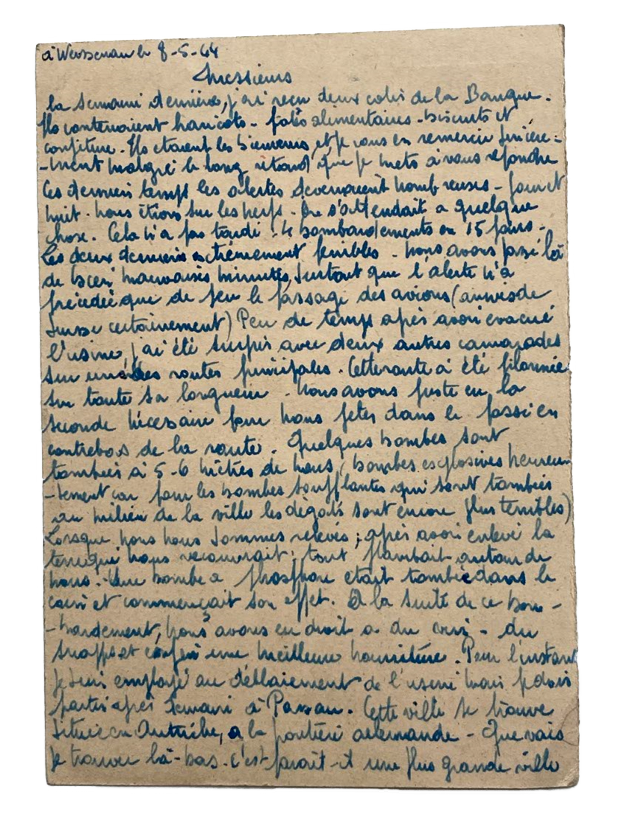

In the autumn, the cold settled in and the long-awaited permits failed to arrive. Claude and his comrades escaped the typhus that hit a nearby camp. In November, they were transferred to Weissenau, 20km from the factory: hygiene conditions were better, but food was even scarcer.

Spring 1944 saw the first air raid alerts. Claude wrote: “I was caught with two other comrades on a main road […] Some bombs fell five to six meters from us.” They all got away unscathed. Soon after, he was sent to Passau (Austria), where housing conditions deteriorated, but food improved.

The return to France and the end of an unwanted journey

Claude Dené finally returned to France on 23 May 1945, after more than two years of forced labour. He rejoined the BEM workforce on 1 July 1945. He remained there until 1949, when he resigned for personal reasons.

Claude Dené’s clear and measured testimony embodies an often forgotten memory: that of the French workers sent to Germany against their will. His letters testify to a human and historical experience that was both personal and widespread.

To go further:

Discover our special feature: BNP Paribas at the heart of the Second World War