Bonaparte and Josephine tie the knot at n°3 rue d’Antin

The BNP Paribas headquarters at 3 rue d’Antin in Paris was the scene of a historic event, the civil wedding of Napoleon Bonaparte and Josephine de Beauharnais.

This came about because the mansion, which was built in the 1720s and originally known as the Hôtel de Mondragon, was confiscated and declared national property during the French Revolution. It was turned into the town hall of the Paris 2nd District, which was the official venue for wedding ceremonies, among them that of the future French Emperor. The building was later re-sold into private hands and when the Banque de Paris et de Pays-Bas (Paribas) was formed in 1872, the Bank set up its headquarters there.

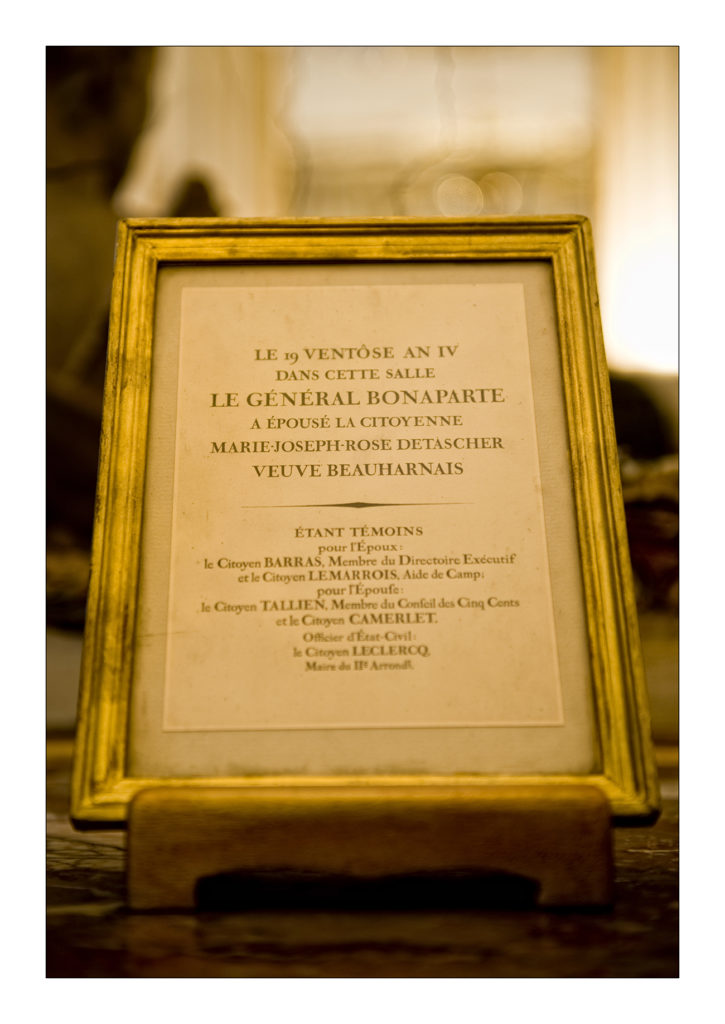

On the evening of what the French Republican calendar called 19 ventôse (‘Windymonth’), Year IV’ – i.e. 9 March 1796 under our system – Citizen Charles Leclerq, an official of the Civil Authority, registered the announcement of the marriage of the young Corsican-born general Napoleon Bonaparte (then written in Corsican spelling as Napolione Buonaparte) and Marie-Joseph-Rose Detascher, ex-Viscountess de Beauharnais, the future Empress Josephine.

Jacques-Olivier Boudon, President of Napoléon Institut and Professor at La Sorbonne, tells about the amazing wedding of Napoléon Bonaparte and Joséphine de Beauharnais at 3 rue d’Antin in Paris.

A marriage certificate riddled with irregularities

Firstly, Bonaparte is described as Chef de l’Armée de l’Intérieur (‘Head of the Home Army’), whereas in fact he had just been appointed Head of the Army of Italy. As a gallant gesture towards Josephine, his age was increased by 18 months. However, in stating his date of birth as 5 February 1768, he effectively gave up his status as a French citizen as although France had purchased Corsica from the Republic of Genoa in 1768, the island was only officially united with France on 15 August, exactly one year before Bonaparte’s real date of birth, 15 August 1769. Moreover, the future Emperor gave his home address as rue d’Antin, i.e. the actual town hall.

As for Josephine, she was made four years younger, her birth year being entered as 1767 instead of 1763.

Josephine and the witnesses arrived in time for the ceremony, set for 8pm, but were kept waiting for Bonaparte for over two long hours. On the eve of his departure for the campaign in Italy, the young general had a huge amount of work to do…

Although it dates from after the wedding – it was actually written up in 1829 – the excerpt from the Civil Register which the Bank displays in the Wedding Hall has considerable historical value. It is a written account of the event, although the original Paris Civil Register was destroyed by fire during the Paris Commune upheavals in 1871.