Looting and restitution : the BNCI and the Rosenberg case

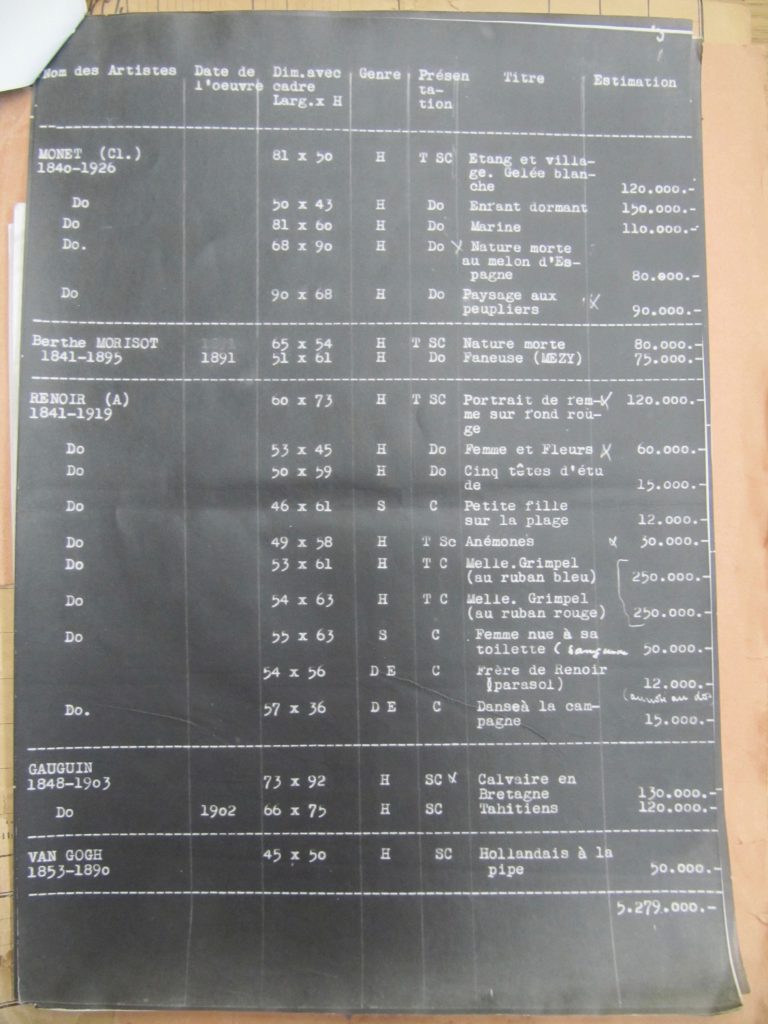

This commemorative plaque was affixed in 2018 to a former BNCI branch in Libourne at the initiative of Anne Sinclair, granddaughter of Paul Rosenberg.

A promoter and champion of modern art, Paul Rosenberg was also a major dealer in Impressionist art. After fleeing Paris, he placed 162 works in a BNCI vault in Libourne to protect them from the threat of bombs. In 1941, they were looted by the Germans.

This example of theft suffered by the Rosenberg family reflects the large-scale looting policy implemented by the Nazi regime against Jewish families during the Second World War. All of these seizures were documented and the documents preserved. Since the end of the Second World War, three restitution campaigns have been carried out to reunite families with their belongings.

Art dealer Paul Rosenberg (1881-1959)

Paul Rosenberg played a key role on the Parisian art dealing scene in the first half of the 20th century. He was “the dealer of the avant-garde”, having worked hard to promote artists such as Picasso, with whom he was very close and acted as global representative, Braque and Matisse. He also had a considerable personal collection of paintings by Picasso, Matisse, Delacroix, Ingres, Corot, Courbet, Gauguin, Monet, Manet, Renoir and others.

He carried out his dealing activities from the ground floor and the first floor of his mansion at 21 Rue La Boétie in Paris, acquired in 1908, the upper floors being reserved for his personal accommodation and that of his family.

In March 1939, he had to close his Parisian gallery and, in the autumn, seek refuge with his family in Floirac, near Bordeaux. He managed to salvage some of the paintings from his gallery and his personal collection – storing some securely in a depot in Tours, in the name of his driver Louis Le Gall, and placing a collection of 162 paintings in a vault at the Banque Nationale pour le Commerce et l’Industrie (BNCI) in Libourne – before leaving for the United States in September 1940. These included at least 33 works by Picasso, 18 by Matisse, 15 by Braque, 13 by Marie Laurencin, 10 by Renoir, eight by Corot, seven by Bonnard, six by Sisley, five by Courbet, five by Manet, five by Utrillo and three by Vuillard.

Find out more

The looting of Paul Rosenberg’s collection

In the summer of 1940, a vast operation began in Paris to confiscate artistic property belonging mainly to Jewish families, as well as to opponents of the Third Reich. Initially led by the German Embassy, this assignment was soon entrusted to a special team under the supervision of Alfred Rosenberg, known as the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce.

The mansion at 21 Rue La Boétie was requisitioned. On 11 May 1941, it became the premises of the Institute for the Study of Jewish Questions (IEQJ – Institut d’Étude des Questions Juives), an organisation responsible for antisemitic propaganda under Nazi supervision, led by the journalist René Gérard, then Captain Paul Sézille from June 1941.

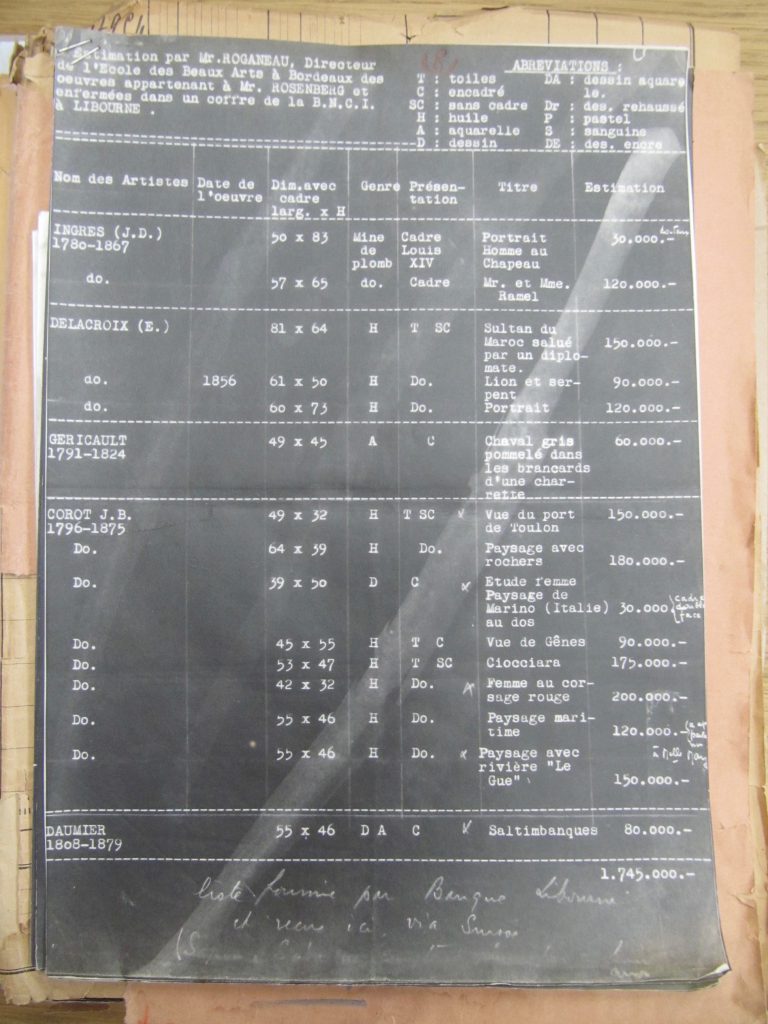

Between 21 April and 6 May 1941, the Germans got their hands on the canvases stored in the vaults of the BNCI in Libourne. The contents of the vault were meticulously inventoried on the orders of the Devisenschutzkommando, the German department responsible for banking supervision, with the assistance of the General Commission for Jewish Questions. On 6 May 1941, François-Maurice Roganeau, director of the École des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, inventoried the 162 works of art found there, before they were transferred to a second vault, which was sealed.

On 5 September 1941, on the order of Wolf Braumüller of the Devisenschutzkommando, the seals were broken by the ERR (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter) and the 162 works returned to Paris, to the Jeu de Paume museum, a centre for sorting and dispersing confiscated artworks.

On 23 February 1942, a decree stripped Paul Rosenberg of his nationality, a preliminary procedure before deportation.

It was from New York, where he had fled in June 1940 and continued his work as an art dealer, that Paul Rosenberg learned of his loss of citizenship and challenged it with the Vichy government.

Code name “Sonderauftrag Linz”

The Linz Special Mission (Sonderauftrag Linz) refers to a vast museum policy conceived by Adolf Hitler, which aimed to enrich the art collections of the “Greater German Reich” with works from Nazi looting or bought cheaply under duress.

Hitler intended to make Linz, the capital of Upper Austria, his native region, a showcase of Nazi culture, with the creation of a huge museum to exhibit masterpieces seized throughout Europe.

Paul Rosenberg was robbed of nearly 400 paintings in three consecutive thefts of his gallery and his personal collection, making him the victim of an archetypal case of mass looting.

Following the Allied victory, a long battle began for the return of his property. Thanks to the meticulous inventory he had made of his works, the testimony of his artist friends, and the Art Recovery Commission set up by the Resistance artist Rose Valland, he and his family were able to recover some of the works, which would be sold from his New York gallery or donated to museums. A few were kept by the family. Around 60 were never recovered.

Restitution continued after Paul Rosenberg’s death. Even very recently, in an exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in 2012, his heirs spotted Profil Bleu Devant la Cheminée (1937) by Matisse, which was returned two years later by the Norwegian museum Henie Onstad.

Find out more

H. FELICIANO, Le Musée Disparu. Enquête sur le Pillage d’Œuvres d’Art en France par les Nazis [The Disappeared Museum: Investigation into the looting of works of art in France by the Nazis], 1995, 2009.

Rose Valland, a conservation attaché, produced a phenomenal inventory of paintings requisitioned and confiscated by the Germans under the Occupation and stored in the Jeu de Paume museum before leaving for Germany. This inventory was sent to the director of the National Museums Jacques Jaujard (1895-1967) and, following the Liberation, enabled a gigantic search to be launched for works of art stolen by the Nazis around the world.

The Rose-Valland database (MNR) (culture.gouv.fr)

Listen to a podcast by Pascal Deux, Rose Valland, héroïne de l’ombre [Rose Valland, Shadow Heroine – archive], a six-episode series of 25 minutes each on France Culture

E. POLACK and P. DAGEN, Les carnets de Rose Valland: Le Pillage des Collections Privées d’Œuvres d’Art en France Durant la Seconde Guerre Mondiale [The Notebooks of Rose Valland: The Looting of Private Collections of Works of Art in France During the Second World War], Fage Éditions, 2011

E. POLACK, “Rose Valland. de la Résistance Civile au Capitaine Beaux-Arts” [Rose Valland: From Civil Resistance to Captain Beaux Arts], Grande Galerie. Le Journal du Louvre, issue 65, winter 2023-2024, p. 64-69

What the archives teach us

Meticulously recorded and archived, the documents are located in two funds:

The National Archives of France in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine retain the gallery’s “aryanisation file”, recorded in the sub-series AJ38 2818, file 3893.

This gives an understanding of the looting process designed to economically eliminate the “Jewish” art dealer.

The Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in La Courneuve house:

209SUP/717 - Summary table of thefts of paintings from the Paul Rosenberg collection, compiling requests made by Paul Rosenberg in the immediate post-war period. This is illustrated by 450 digitised photographs of unclaimed works that are actually from his stock or private collection.

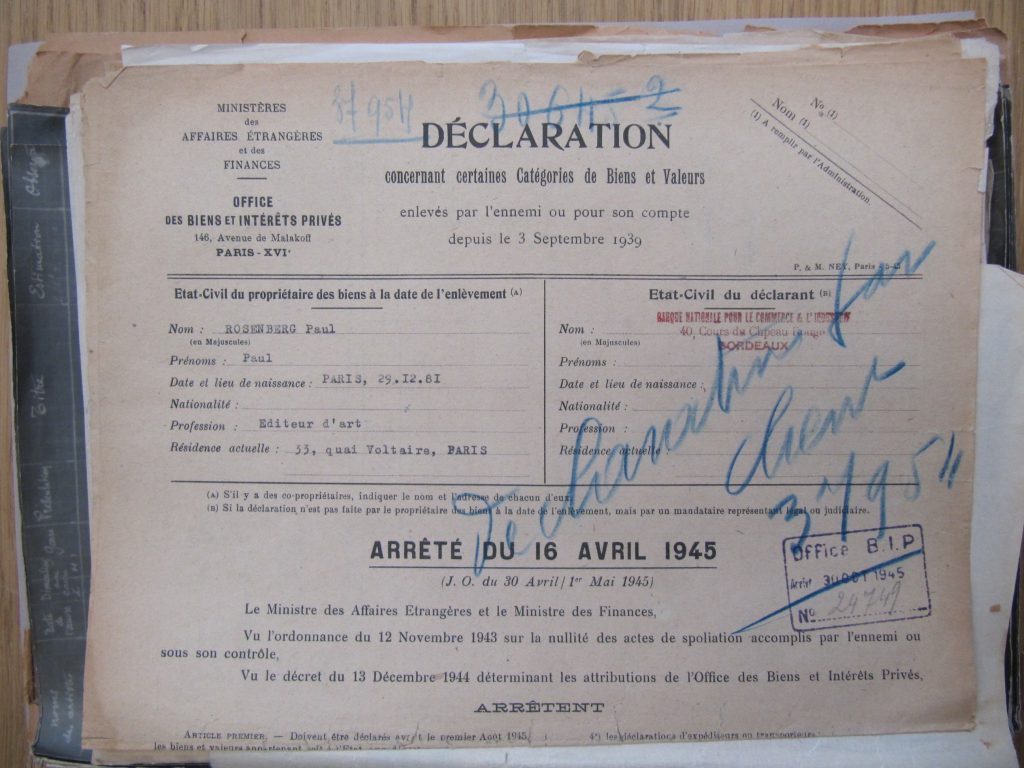

13BIP/162, file 37954 SPAF file (German looting in France) Rosenberg Paul (wife of Marguerite Ida née Loevi), CRA (Artistic Recovery Commission). Declared by BNCI Bordeaux on 23 July 1945 and Paul Rosenberg on 30 July 1945.

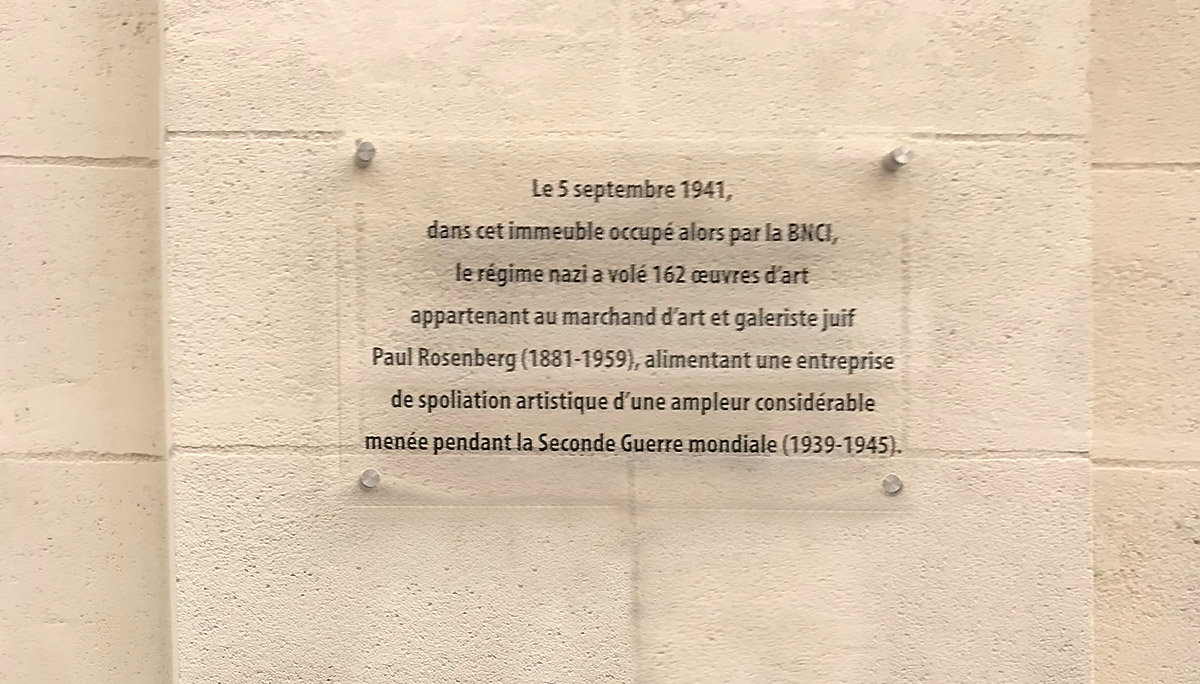

The file contains: - the photocopy of the receipt from the DSK, 5 September 1941, attached to a letter from the BNCI of 15 July 1960, addressed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs/OBIP, “returning the photocopy of the receipt for 162 paintings confiscated by the German authorities from Mr Paul ROSENBERG"

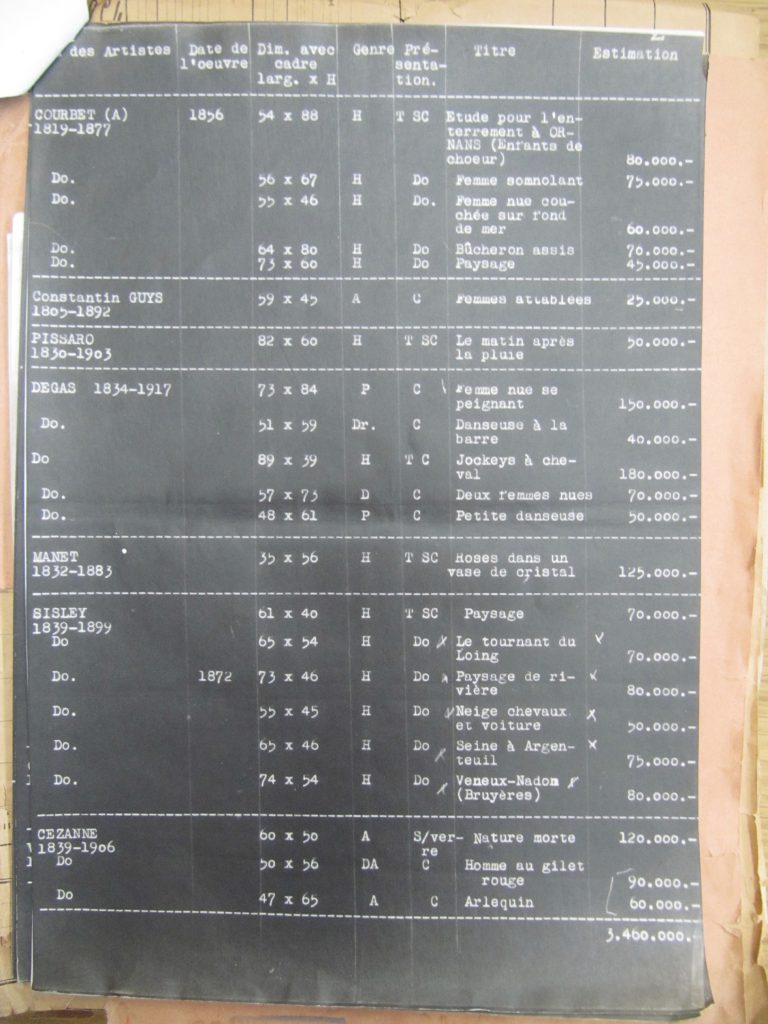

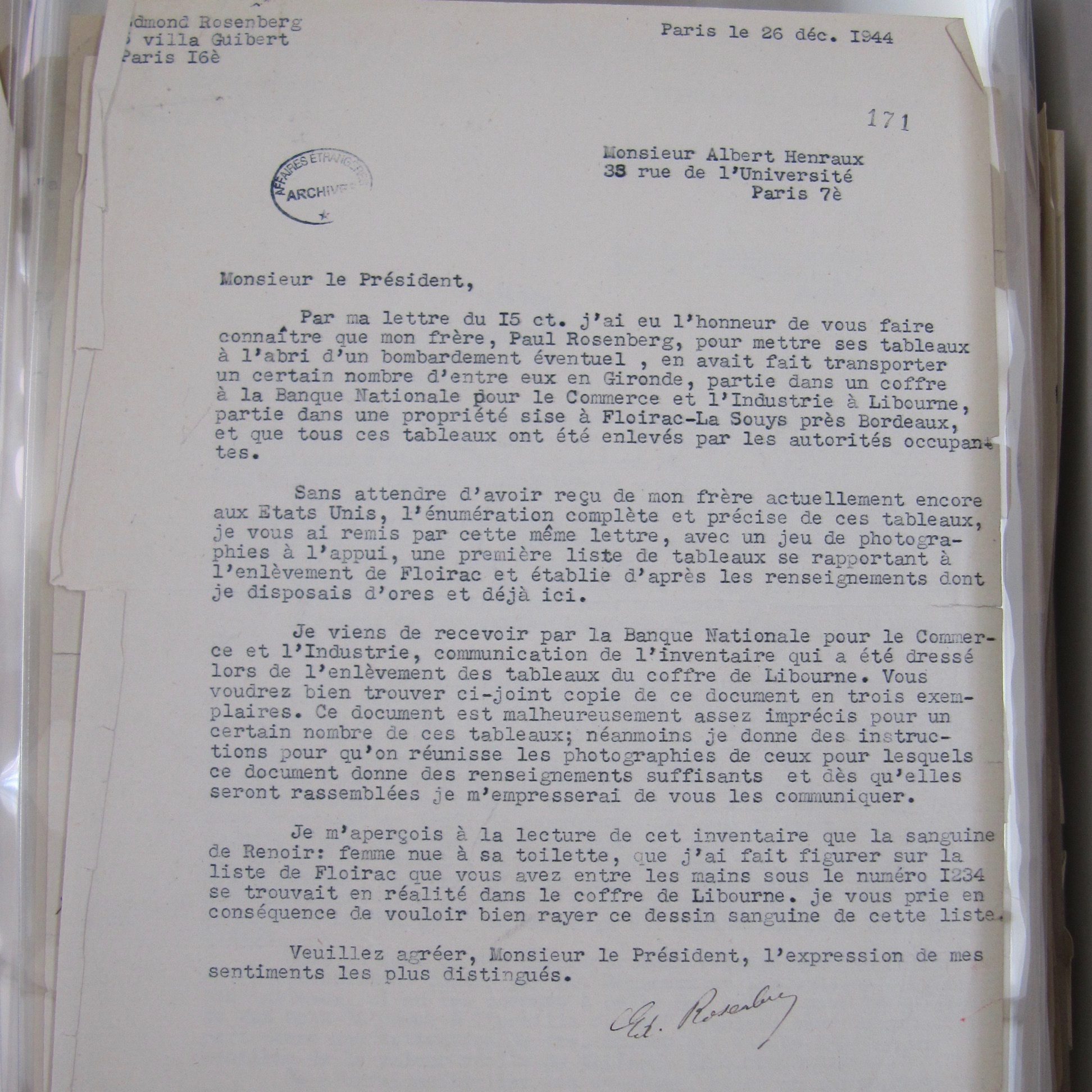

- the list provided by BNCI: the estimate given on 6 May 1941 by Mr Roganeau, director of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, of the works belonging to Mr Rosenberg and locked in a BNCI vault in Libourne (copy). The document states that the list is provided by the bank.

- summary report on the conditions under which the looting was carried out, dated 1945, and which quotes the letter from Edmond Rosenberg from CRA file 115, as well as various associated supporting documents, including a copy of the receipt from the DSK and a photographic reproduction of the inventory of paintings removed from the BNCI by the German authorities.

209SUP/1 file 45. 151 - Individual file submitted to the Artistic Recovery Commission. The circumstances in which the paintings were removed from the Libourne vault are repeated in various documents, and the same circumstances are recounted.

Looting and restitution in France

First stage: 1944-1954

In France, the looting of the property of persons deemed to be Jewish during the Occupation lasted four years.

From 1944 to 1954, the French State pursued a policy of restitution: there was almost no public debate on restitution, demonstrating a desire to restore the rights of victims of looting.

Implementation of this policy began in Algiers, before becoming widespread with the liberation of France from 1944. The series of measures was introduced – from the immediate release of bank accounts in August 1944 to the law on the reimbursement of withdrawals made from blocked accounts (June 1948) and the creation of a Commission for the choice of recovered works of art that could not be returned (June 1948).

In the 1950s, the Office of Property and Private Interests (OBIP) had received claims for some 100,000 items of property “stolen by the enemy” although the owners of some property had not been identified.

In Germany, following diplomatic intervention and in successive stages in 1957, 1961 and 1964, the BRüG law (Bundesrückerstattungsgesetz) gradually opened up the possibility of compensation for those whose property had been seized, particularly the victims of the looting of apartments.

The Unified Jewish Social Fund (FSJU) took over most of the management of claims files. This compensation was in addition to the war damages already paid, although it was the first possibility of compensation for artworks, as war damages in France had not covered luxury items.

Second stage : since 1995

In the 1990s, awareness of genocide became a major, publicly shared reality. The national narrative of the war years, which had up until then focused on fighting, the Resistance and Collaboration, now focused on victims. The proliferation of historical research, the Eichmann trial and the Six-Day War also played a role. At the same time, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the voices of “double victims” in former Eastern Bloc countries – those who suffered from Nazi “Aryanisation” followed by communist nationalisation – began to be heard.

In France, in 1995, President Jacques Chirac recognised the collaboration of Vichy France on the anniversary of the Vélodrome d’Hiver roundup. The French media took up the issue, condemning the presence of artworks stolen from Jewish families in French museums.

The Mattéoli mission

In March 1997, a mission to study the looting of the Jews of France – known as the Mattéoli mission after its president – was set up in order to assess the amount of property likely to remain unclaimed in government agencies and companies. The mission’s General Report estimated that the remaining unreturned property accounted for between 5% and 10% of the total calculable value of the looted assets and around 25% of the original owners.

Artworks and bank accounts were highlighted by the press, echoing actions taken across the Atlantic, where class actions threatened to ban European companies from operating on American soil. Swiss and then French banks were affected between 1996 and 1998. Stolen works of art were meanwhile described as “the last prisoners of war” by the president of the World Jewish Community (WJC).

At an international conference held in December 1998, France undertook to respect the new “Washington Principles” by giving itself the means to reach a “fair and equitable solution” concerning works confiscated by the Nazis and not returned to their owners.

The CIVS

Based on the mission’s recommendations, the individual compensation file was reopened, with the creation in September 1999 of the Compensation Commission for Victims of Looting (CIVS) which occurred due to the anti-Semitic legislation in force during the Occupation. This Commission was tasked with examining individual claims submitted by victims or their heirs for compensation for damage resulting from the looting of property, due to the anti-Semitic legislation adopted during the Occupation, by both the occupying forces and the Vichy authorities. The Commission was made responsible for drawing up and proposing appropriate redress or compensation measures. It could issue any useful recommendations, particularly with regard to compensation. In November 2000, the amount of unclaimed property estimated by the Mattéoli mission was paid to a specially-created Foundation for the Memory of the Shoah.

The CIVS works in collaboration with all banks (which keep their customers’ files) and relies on the banks’ recommendations to decide on redress and compensation measures for claims submitted to it.

BNP Paribas has processed more than 634 requests since the Commission was established in 2000.

By 2022, this second stage of restitution appeared to be coming to an end. After peaking in the early 2000s, the number of requests – for all types of property – sent to the CIVS was steadily falling. Of the 30,000 requests received in 20 years of existence, two-thirds related to the looting of apartments and the seizures of professional property, while the remaining third related to bank seizures.

With regard to unclaimed bank assets, France and the United States have agreed on a method of compensation combining French criteria (prior study of the facts) and the American approach (allocation of a lump sum).