When Female Colleagues Step Out of the Shadows

Since the late 19th century, they have been the silent wheels of the financial machine. In separate workspaces, women have been working diligently. However, they fully took their place in the banking sector in the mid-20th century.

The Bank: A Historically Male-Dominated World

Women’s work did not begin after World War I. From fields to domestic work, they have long occupied necessary functions for the smooth operation of the economy. During the second half of the 19th century, women working as domestic employees made up 12% of the active population. And in factories, two million female workers were already at work on the eve of the war.

It is worth recalling that at this time, the status of married women, established by the Napoleonic Code, placed them under marital tutelage and deprived them of their legal capacity, just like children. It was not until the end of the 19th century that the first women set foot in banking. Since then, they have never left.

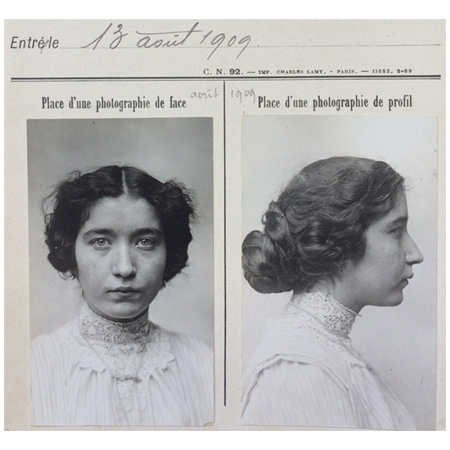

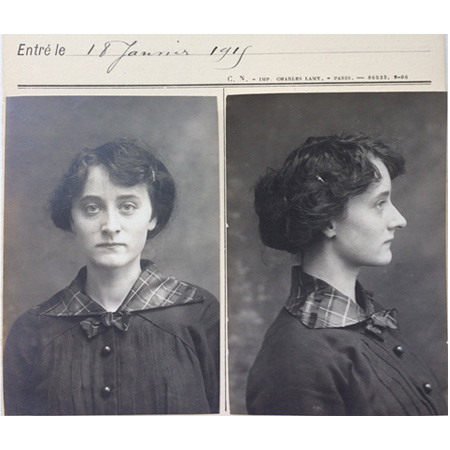

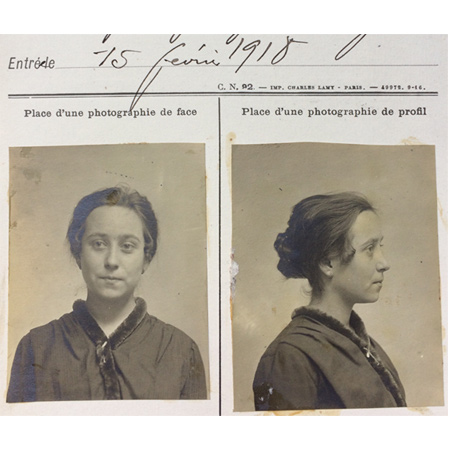

The Discreet Entry of Women into Banking

With the creation of administrative services in the 1880s, women entered the banking world.

This dynamic was not limited to banks. The growth of office work, since the commercialization of the first “Remington No. 1” typewriter in 1874, echoed the qualities then attributed to women: “meticulous”, “applied”, and “honest”. The profession of typist remained largely female until its disappearance at the end of the 20th century.

These workers were mostly from the middle class. They had diplomas attesting to their competence in the profession they exercised. Access to education for young girls and women progressed significantly in the 19th century. The university opened its doors to women in the 1860s, and the Jules Ferry law of March 28, 1882, made education compulsory for all, facilitating access to new professions. Work was then considered a tool for emancipation by the first feminist movements.

Working Conditions

These women receive a lower salary than their male colleagues. They often have only an auxiliary status, with little hope of being promoted internally. Most of them meet temporary needs: they are hired only to be laid off later. It was precisely to combat this precarious status that the women employed on a daily basis at the CNEP created, as early as 1902, a mutual aid society aimed at financing benefits in case of absence due to illness.

Women worked behind the scenes. They evolved in administrative services, such as in the recovery office, accounting services, and especially in the securities and coupons office. They had no contact with customers or with their male colleagues. They ate and worked in separate rooms. In some banks, they even entered through a special staircase.

Specialized White-Collar Workers

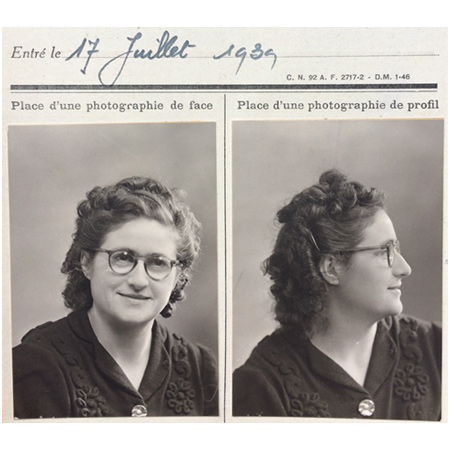

The integration of women accelerated in the 1930s, with the creation of “back-offices”, where all administrative functions of a region were centralized. Many women found themselves in these new “tertiary factories”.

They were then at the forefront when the mechanographic revolution transformed office work. These machines made it possible to automate calculations and greatly simplify administrative tasks. Even in the shadows, female bank employees became icons of the mechanical banking revolution and mass information processing.

The introduction of computers in the 1960s led to the gradual automation of work. As more and more women entered the workforce, they also acquired computer skills and began to pursue careers in the field of computer science.

![In the BNCI computer room, an operator controls an IBM 705 computer, [1957-1961], reference11Fi747-2 – Historical Archives BNP Paribas](https://histoire.bnpparibas/wp-content/upload/2025/09/2-IBM-705-11FI747.png)

The Revolutions of the 20th Century

In the banks that would eventually become part of the BNP Paribas group, women became increasingly numerous. Whereas they represented in 1914 only 25% of the staff of the Comptoir national d’escompte de Paris (C.N.E.P.), they were 51% in 1976 at BNP. During the 1970s, the number of “graded” women also exceeded the number of “employed” women.

Certain professions remained very feminine, such as that of switchboard operator. In the 1950s, the first mixed company restaurants opened for staff.

Sign of this new era: women moved from the shadows to direct contact with customers. Whether in a consulting role or as a cashier, they proved that their skills were not limited to administrative tasks. However, certain professions were still considered feminine, such as that of receptionist.

“Today, governments and large retailers, banks and industries, private companies and public services have all come to realize that to achieve true success, they must start with the basics – namely, welcoming their customers. It’s a huge ‘Operation Smile’ initiative.”

L’Est Républicain, date unknown, just prior to March 1971

Making a Place for Oneself in an Increasingly Welcoming Bank

Just before the 1980s, a new dynamic emerged: making the bank more welcoming to women. In this context, more and more female colleagues finally broke through the glass ceiling. In 1978, 14% of BNP’s executives were women. In 1990, they were 23%.

These figures indicate a strong trend: women who wanted to make a career were no longer officially hindered, although their role within the family cell was still considered “specific”.

Across the five continents where BNP operates, women have become an integral part of the banking industry. Notably, in Singapore, as of 2008, women made up 45% of managers, surpassing the 40% mark in France.

The “Giscard” law of January 1981 led to a surge in part-time work, enabling women to strike a better balance between their family responsibilities and their careers. While women have been more likely to take advantage of this option than men, it’s not a universally popular choice. By 1987, 20% of women were working part-time. Notably, as women advance in their careers, they are less likely to choose part-time work, opting instead for full-time positions.

The 21st Century: Evolution in Progress

Since 1880, female employees have therefore come out of the shadows, and women are now recognized as full-fledged bank colleagues. To ensure that this commitment does not remain a dead letter, the Group signed the Diversity Charter in 2004 and was the first bank to receive the “Diversity Label” in 2009 for its proactive policy.

These recent advances would not have been possible without the action of the female colleagues themselves, who were the first to be concerned. They took their destiny into their own hands in 2004 by creating a working group in Human Resources, tailored for and by the bank’s female executives: MixCity was born! The network acts to “propose measures facilitating the lives of women in the company and promoting their access to higher management positions” (BNP Annual Report 2008. BNP Paribas Historical Archives).

In 2009, MixCity grew and became an association, a pillar of the promotion of internal and external diversity within BNP Paribas. At the same time, this type of association spread throughout the Group, such as in London (Women’s International Network), New York (Diversity Council), or Bahrain, where over 200 people, including members of the royal family, responded to BNP Paribas’ invitation to a conference on “Women and Leadership”.

Elisabeth Karako is the founder and Director of the “Diversity Group”, during this pivotal period. She accompanied the development of MixCity, facilitated its transformation into an association, and obtained the “Diversity Label” for BNP Paribas in 2009.

For a balanced representation between women and men in the governing bodies, the BNP Paribas group had set itself the goal of reaching 40% of women by 2025 on its Executive Committee: an objective exceeded with 42% of women since July 1, 2024.