The predecessor banks in Le Havre: financing Reconstruction

The city of Le Havre, destroyed by 80% due to the bombings it suffered during World War II, is a symbol of the extent of the destruction, but also of the rapidity of Reconstruction. The port city, with its architecture steeped in tradition, gives way to a rethought urban center designed by architect Auguste Perret. Its port, rebuilt and modernized, experiences a new phase of development during the second half of the 20th century. The predecessor banks of the BNP Paribas Group are both actors in the Reconstruction, but also affected by the destruction.

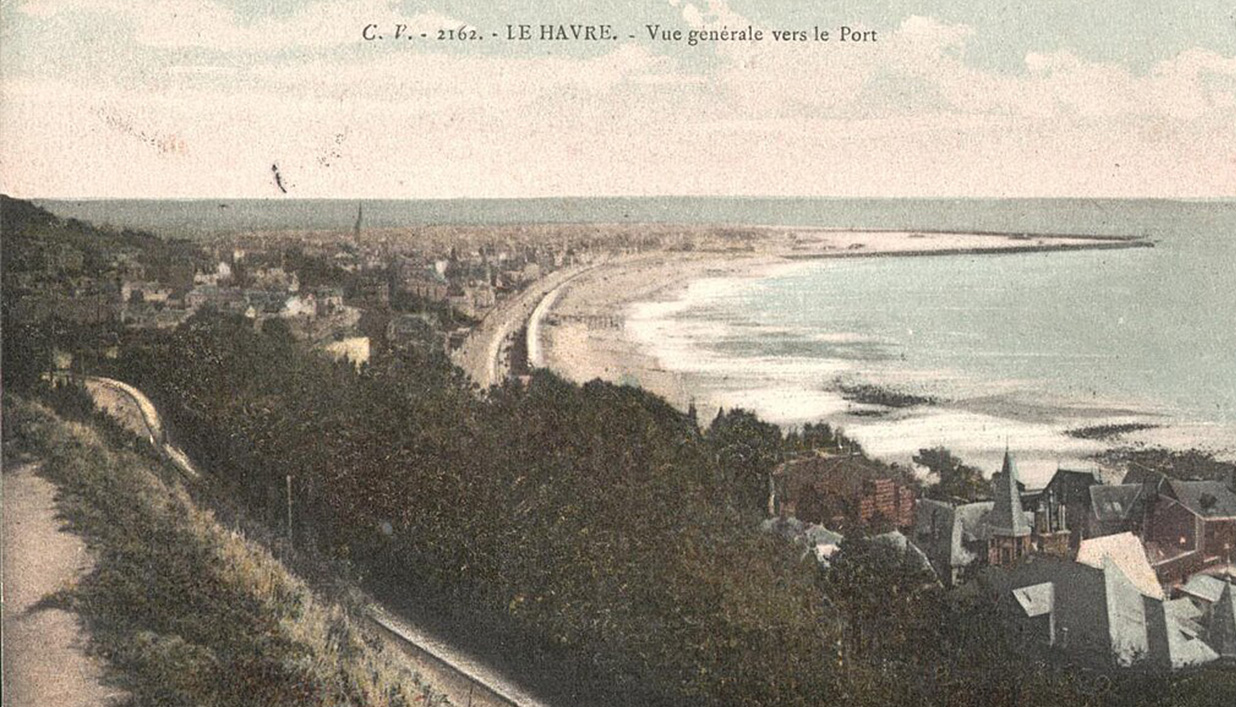

Le Havre, before World War II: a port city with intense economic activity

Founded under the auspices of Francis I, who signed the city’s foundation charter in 1517, the city of Le Havre was created on the right bank of the Seine estuary. This foundation was primarily that of a new port, intended to compensate for the silting up and inadequacy of older ports, such as Rouen or Honfleur. The goal was thus to facilitate the supply of the capital, Paris, while having a military base that controlled access to the Seine.

A military base, but also a shipyard, fishing port, and departure point for numerous expeditions to the Americas, many products, such as sugar and coffee, are imported through the port of Le Havre. The city, born in the Notre-Dame neighborhood, develops with the Saint-François neighborhood, featuring Renaissance architecture designed by Girolamo Bellarmato. It is a modern city with a dynamic economy, but one that will nonetheless be marked by the Wars of Religion. The port is modernized in the 17th century and becomes a hub of the modern economy; the French East India Company establishes itself there in the 1640s. The trade in exotic products develops, and the port also becomes a stop in the French triangular trade. From the Seven Years’ War to the French Revolution, the city and port are impacted by successive conflicts, as well as the war with Great Britain under the Empire, which hinders port trade.

In the 19th century, the city of Le Havre experiences significant demographic growth. The Chamber of Commerce is established in 1802, housed in the Stock Exchange building, which was constructed in 1784. The second half of the 19th century is a very prosperous period for the port of Le Havre, which undergoes deep modernization. In 1847, the railroad arrives in Le Havre. The general warehouses are completed in 1860, following the construction of the docks. A first steamship line to New York is established in 1831, marking the beginning of transatlantic travel. By 1896, the city of Le Havre has a population of 119,500 inhabitants. The port of Le Havre is the entry point for goods such as cotton and coffee.

In 1914, Le Havre is the leading port in Europe for coffee imports!

“In front of the Place de la Bourse Roland paused, as he did every day, to gaze at the docks full of vessels–the _Bassin du Commerce_, with other docks beyond, where the huge hulls lay side by side, closely packed in rows, four or five deep. And masts innumerable; along several kilometres of quays the endless masts, with their yards, poles, and rigging, gave this great gap in the heart of the town the look of a dead forest.”

— Guy de Maupassant, Pierre and Jean, 1888

World War I spared the city, but the human toll was heavy among the 25,000 people from Le Havre who went to the front. The interwar period marked a time of economic slowdown, exacerbated by the impact of the 1929 crisis. The 1930s also saw the opening of the Gonfreville-l’Orcher oil refinery in 1933, a milestone in the transformation of port activities, which would shift towards petrochemicals after World War II.

By 1939, the city had surpassed 160,000 inhabitants. Around the historic center, it had expanded to encompass the surrounding villages, which had become neighborhoods of the city, such as Graville, a village that was annexed by Le Havre in 1919.

The prospect of conflict put the business world in Le Havre on hold. As the leading French port in terms of value and the second-largest French port after Marseille in terms of tonnage, the main imported products at the time were still coffee, cocoa, and other goods from far away.”

World War II

On May 19, 1940, the city was hit by a first German bombing raid, and by June 1940, it was occupied by German troops. The city lived under the rhythm of requisitions and raids imposed by the Occupation, and suffered numerous Allied air attacks between 1940 and 1944, as the port was a strategic location. In 1940-1941, the air attacks carried out by the Allies primarily targeted the port, with the goal of preventing a German landing in England. From 1942 onwards, the attacks aimed to hinder the construction of the Atlantic Wall, and intensified in 1943 with the preparation for the June 1944 landing.

After the Battle of Normandy on August 21, 1944, the Allies turned their attention to the port of Le Havre. At the beginning of September, the evacuation was interrupted, and the bombing raids dropped approximately 10,000 tons of bombs on the city between September 5 and 10, including 1,880 tons on the historic center. The city was liberated on September 12, 1944. 10,000 buildings were destroyed, and 2,000 had to be demolished due to extensive damage. 2,000 people from Le Havre lost their lives during the bombing.

After the conflict, the port and the city were unrecognizable, and activities had to resume despite nearly 80,000 people from Le Havre being left homeless.

The reconstruction was entrusted by the Ministry of Reconstruction and Urban Planning (MRU) to the renowned architect Auguste Perret, who, along with his former students, created a workshop to respond to what would become one of the most ambitious reconstruction projects in France: 10,000 housing units, office and commercial buildings, and the recreation of an urban fabric. The city became a showcase for modern urban planning and architecture, with Perret’s team designing a new city center that would be both functional and aesthetically pleasing.

Reconstruction and the ‘MRU‘

The Ministry of Reconstruction and Urban Planning (MRU) was created on November 16, 1944. Its action is multifaceted, and aims at clearance, demining, and reconstruction, particularly of housing. At the end of World War II, France indeed had 5 million people declared as victims of war damage and 2.5 million destroyed buildings.

The predecessor banks of the BNP Paribas group, present in Le Havre, are directly affected by the conflict. They are also, for some of them, involved in the Reconstruction, to which they contribute financing, notably through groups of war damage victims.

The predecessor banks in Le Havre

The CNEP branch

The Comptoir national d’Escompte de Paris, one of the predecessor banks of the BNP Paribas group, established a branch in Le Havre in 1890. Located at 2 Rue de la Bourse – later renamed Rue Jules Siegfried during the first half of the 20th century, near the City Hall, the branch was situated at the heart of Le Havre’s economy.

For the Comptoir national d’escompte de Paris (CNEP), one of the predecessor banks of the BNP Paribas group, the Le Havre branch, in connection with international trade, serves as a link with its international network of branches located in countries that export raw materials imported to France through the port of Le Havre.

The CNEP develops its bank network

Its location, advantageous for participating in the economic life of the port city, places it at the heart of the area bombed by the Allies in 1944. The building is completely destroyed, as are the iconic buildings surrounding it, such as the City Hall and the Le Havre Stock Exchange, built in 1880, of which only the facades remain.

Reconstruction is a prerequisite for continuing the agency’s activities, which sets up a temporary office. However, the CNEP’s management must take into account the change in the bank’s status, which was nationalized in 1946.

The building is rebuilt a little further away, at 144 Boulevard de Strasbourg. The agency will be located in the basement, ground floor, first and second floors. The procedure for compensation for war damage is long and complex, especially since the establishment encounters several setbacks: in the early 1950s, an error is discovered in the estimation of the damaged agency’s surface area. The activity also requires planning, as before the war, for two functional apartments. The new director’s apartment, located on Avenue Foch, whose purchase is approved at a Board of Directors meeting in 1953, does not have a service room, so it is necessary to acquire an additional small apartment.

Perret’s project also presents incompatibilities with the image that CNEP’s management wants to convey. In 1955, the bank grants a new loan to meet different needs. The facade cladding planned in the overall project is in “washed gravel, aggregates of white cement fragments and gravel” which the management does not like. The architect in charge of the project proposes a stone facade.

Construction is underway, and then the agency needs to be furnished. The safes intended for customers are installed in 1958, in a city still under construction. A rotating guard system, ensured by the agency’s employees, is established to ensure the security of the safes and their contents. (Sources: CNEP archives, real estate series 207AH177)

The BNCI branch

The National Bank of Commerce and Industry (BNCI) has a branch in Le Havre, comprising the branch, an office, and an agency in Fécamp. The inspection reports of the branch are laudatory, and highlight the competence of the employees, both in the management of the branch and in maintaining relationships with entrepreneurs and representatives of the Havre economic life.1

Before the BNCI, the National Credit Bank (BNC) had an agency located at 97 Boulevard de Strasbourg, previously under the umbrella of the Comptoir d’Escompte de Mulhouse (CEM), and which played an important role in financing the cotton trade.

In the report presented to the General Assembly in 1916, the BNC, created in 1913, draws a positive balance of its first years of existence: “Almost all of our branches have contributed to this expansion, but circumstances have particularly favored our branches in Paris, Lyon, Le Havre, and Marseille” (General Assembly Report of April 12, 1948, 12AQ033).

The BNC is also responsible for the purchase, approved by the board of directors on December 24, 1919, of the building at 81 Boulevard de Strasbourg, which forms a block previously occupied by the Grand Hôtel Moderne, between Boulevard de Strasbourg and 16, rue Jules Lecesne.

Equipped with a glass roof and a facade bearing the name “Banque Nationale de Crédit”, the branch, with its carefully designed architecture, has an interior courtyard and housing for the management. It escapes the bombings of 1944 and also testifies to the pre-war architecture of Le Havre. Built in 1900, the building was transformed into a branch by the architect André Houdaille, who would later participate in the reconstruction project led by the Perret workshop after the war. The building retains some of the most emblematic elements of the hotel.

After the liquidation of the BNC, the BNCI adds the Rond-Point agency to this complex in 1932, which was also spared by the bombings.

In 1947, the branch and its agencies have fewer agents, and the summary aspect of the Rond Point agency is even noted by the BNCI management. However, the Le Havre buildings of the bank, which were relatively spared by the bombings, allow the branch to resume its activities in a city where everything needs to be rebuilt.

In 1966, the CNEP and BNCI merge to form the Banque Nationale de Paris (BNP). The Le Havre branch expands: the Havre-Rond Point office is maintained, as is the Fécamp agency. The Bolbec agency is added, as well as permanent offices in Lillebonne, Harfleur, and Le Havre rue d’Etretat in the 1960s. The development of the branch continues with the creation of other permanent offices.

The Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas

The Bank of Paris and the Netherlands has long-standing ties with companies in Le Havre. It finances some of them, such as the Tréfileries and Laminoirs du Havre2, which specializes in copper and alloy work, with the port of Le Havre being the leading importer of copper from North America at the time – established in 1896. After World War II, the Bank of Paris and the Netherlands mobilized its institutional network to position itself as a leading bank for the reconstruction of Le Havre, which included the city, the port, and various groups of victims.

The organization of the Reconstruction took shape from 1947 with the adoption of the Monnet Plan and various finance laws, which coordinated investment efforts and economic recovery. Banks played a crucial role in financing various sectors and participated in the Reconstruction, which was also a modernization of the economy.

Each sector or group had one or more leading banking establishments. In 1948, the Bank of Paris and the Netherlands positioned itself as the leader in the reconstruction of the port of Le Havre. It also participated in the financing of certain groups of victims, such as the Group for the Financing of Immobilier Reconstruction in Le Havre in 1947. In a note dated December 2, 1947, its representatives explained the bank’s position: “The Bank of Paris and the Netherlands – an investment bank – does not have a particular vocation to deal with immobilière reconstruction, it only wanted to reserve its rights when, due to its activity or requests made to it, it had been led to initiate the construction [of groups of victims] […] The Bank of Paris and the Netherlands has a particular vocation to provide its support in the industrial domain”.

During the reconstruction, BNP Paribas’ predecessor, Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas, participated in the refinancing of the economy, but by focusing on industry, it strengthened its strategy as a investment bank and its international positioning, which it would implement during the second half of the 20th century.

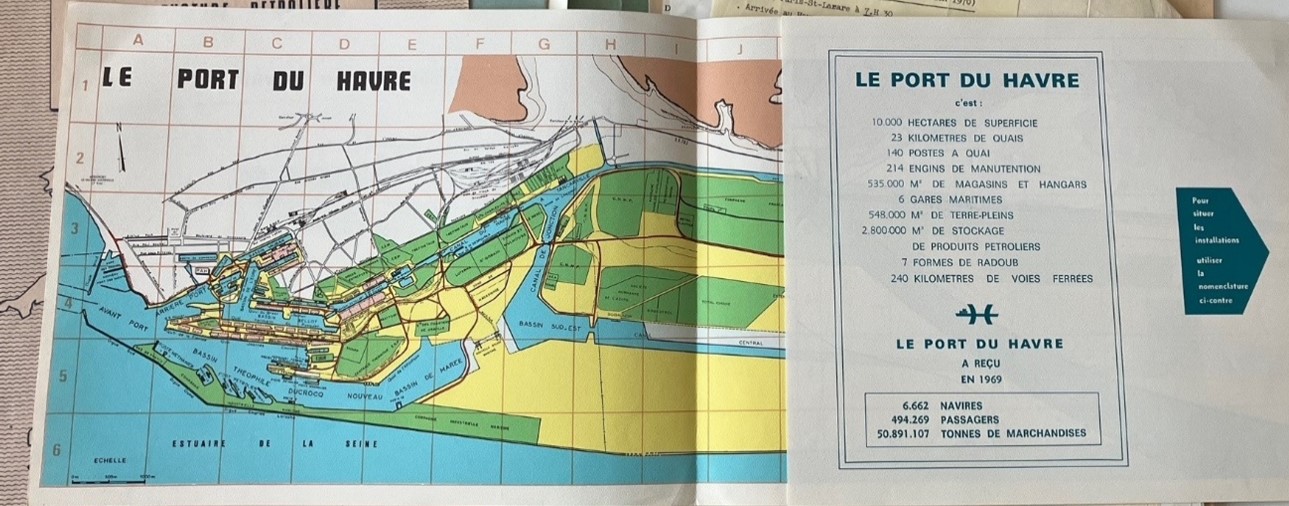

The Port of Le Havre

In 1944, the reconstruction project for the Port of Le Havre was colossal. More than 80% of the quays were damaged or destroyed, as were most of the machinery, and the basins were cluttered with sunken ships. The port, which had been autonomous since the decrees of April 20, 1928, and October 25, 1935, was authorized to contract a loan to finance the reconstruction of the facilities, which would take place over a period of 20 years.

To go further (French resources):

La Reconstruction en Normandie et en Basse-Saxe après la seconde guerre mondiale – Chapitre 9. Le spectacle du logement ordinaire et la normalisation du quotidien dans les appartements-types de la reconstruction – Presses universitaires de Rouen et du Havre

André Corvisier (dir.), Histoire du Havre et de l’estuaire de la Seine, Toulouse, Privat, 1987

Armand Frémont, Mémoires d’un port, Paris, Arlea, 1997

Commémoration des 80 ans du ministère de la Reconstruction et de l’Urbanisme

Photothèque du ministère de la Reconstruction et de l’Urbanisme

Le Havre, patrimoine mondial – l’Hôtel de ville

Reconstruire le port du Havre (INA)

La Reconstruction en Normandie et en Basse-Saxe après la seconde guerre mondiale